Currently released so far... 251287 / 251,287

Articles

Browse latest releases

Browse by creation date

Browse by origin

Browse by tag

Browse by classification

Community resources

Thailand - Thailand’s Moment of Truth (Part One of Four)

Andrew MacGregor Marshall

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH

A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM

#THAISTORY | PART ONE OF FOUR | VERSION 1.3 | 240611

Andrew MacGregor Marshall

The battle lines in Thailand’s political environment are clearly drawn... The Thaksin machine faces off against a mix of royalists, Bangkok middle class, and southerners, with Queen Sirikit having emerged as their champion, as King Bhumibol largely fades from an active role. The two sides are competing for influence and appear to believe, or fear, that the other will use the political power it has to marginalize (if not eliminate) the opposing side. They are positioning themselves for what key actors on both sides freely admit to us in private will be Thailand’s moment of truth - royal succession after the King passes away.

- U.S. cable 08BANGKOK3289, November 4, 2008.

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

- Thai proverb

Nothing will come of nothing; speak again.

- Lear to Cordelia in William Shakespeare, King Lear, Act I Scene I

..........

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE.........“THE DYSFUNCTIONAL FAMILY PICNIC”

I....................... “A WATERSHED EVENT IN THAI HISTORY”

II..…..................................“LOVE OF FLYING AND WOMEN”

III....................... “FEAR AND LOATHING FOR THE QUEEN”NOTES:

There are several ways to transliterate Thai into English, and there is little agreement even on basic ground rules. The U.S. cables often use eccentric spelling for Thai names, and often use several different spellings, sometimes even within a single cable. Quotes from the cables and other sources are reproduced verbatim, even if this means conflicting spellings in the text of the article.

I have followed three rules in my redaction policy for this story: 1. If the source of information is a player in the game, their identity is not redacted. 2. The exception to this is if identifying the source could subject them to significant risk of physical harm. 3. If the source is not a player in the game, their identity, and other information that could help identify them, has been redacted. Xs in the text signify redaction. It should be noted that the number of Xs used has been deliberately randomized. Counting the number of Xs will not provide any secret insight into the source.

My name is Andrew MacGregor Marshall. I am not based in Thailand. There is an excellent Bangkokbased freelance journalist called Andrew Marshall, who writes for Time magazine among other publications and authored a book on Burma, The Trouser People. He has nothing to do with this article and obviously should not be held responsible for anything I write.

This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010.

PROLOGUE: “THE DYSFUNCTIONAL FAMILY PICNIC”

Late in the evening of Tuesday October 6, 2009, the world’s longest reigning living monarch, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, Rama IX of the Chakri dynasty of Siam, was restless and alone, unsteadily pacing the corridors of Siriraj Hospital on the west bank of the Chao Phraya river that loops and weaves through the unruly urban sprawl of Bangkok. Bhumibol, a revered ruler whose towering influence during six decades on the throne profoundly shaped the character and destiny of modern Thailand, had been admitted to Siriraj on September 19, a few months before his 82nd birthday, with a mild fever and difficulty swallowing. His recovery was complicated by his Parkinson’s disease and a possible bout of pneumonia, and there were worrying whispers among well-connected Thais that the king was also sunk in deep depression. Even so, by the first week of October his doctors pronounced him well enough to be discharged to the nearby Chitralada Palace, where he had lived for most of his reign. But Bhumibol declined to go home. He remained at Siriraj, in a 16th floor room in a special section reserved for royal use in one of the hospital’s towers. On October 4, a full moon hung in the sky over Siriraj, heralding the start of the holy kathin month in the ancient Theravada Buddhist tradition, an auspicious time for merit making at the end of the rainy season and the beginning the rice harvest. Two nights later, Bhumibol rose from his bed and went for a solitary walk along the quiet hospital corridors.

Pausing at a window and gazing out into the Bangkok night with his one good eye, the king looked across the river, past the soaring silhouette of Wat Arun, the Temple of the Dawn, to the opposite bank and the golden spires of the Temple of the Emerald Buddha and the Grand Palace that for more than two centuries, since the founding of the Chakri dynasty, have represented the heart of spiritual and royal power in Thailand.

They were shrouded in darkness, lost and invisible in the gloom. Bhumibol sent orders that the lights of the Grand Palace were not to be turned off during the night. He wanted to always be able see it from his hospital on the far side of the Chao Phraya.

In Bangkok’s frantic jumble of slums and shophouses, luxury high-rise condominiums and decrepit apartment buildings, stretching away to the horizon from Bhumibol’s hospital windows, and in the constellations of provincial towns and rural villages beyond, many millions of Thais were anxious and fearful of the future. Millions were angry, too. Thailand was troubled and divided, and Bhumibol’s illness seemed to be a reflection of the disorder that afflicted his kingdom, and a disquieting omen of turmoil to come. A decade earlier, brash Chinese-Thai telecoms billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra had launched an unprecedented effort to transform Thai politics with his authoritarian "CEO-style management" of the country. Thaksin had been more spectacularly successful than anyone had expected - so successful that the elderly courtiers and bureaucrats surrounding the king had come to view him as a dangerous rival to Bhumibol and an existential threat to the very survival of the Chakri dynasty. And so Thailand’s establishment had turned on Thaksin. The escalating struggle threatened to tear the country apart, exposing deep ideological, social, regional and economic faultlines that belied the official myth of a harmonious and contented "Land of Smiles". A proud nation that just a few years before had symbolized the emergence of Southeast Asia as a dynamic developing and democratizing region was suddenly flung backwards into conflict, self-doubt and confusion.

For Bhumibol, it was a personal tragedy. In his declining years, after devoting himself for well over half a century to the task of reviving the prestige of the palace as the unifying sacred core around which his country revolved, he was watching his life’s work crumble before his eyes.

Nobody had ever thought he would inherit the throne of Thailand, least of all Bhumibol himself, son of a celestial prince who saw no future for the monarchy and a mother with no royal blood who was orphaned as a child. Bhumibol grew up in Switzerland, a world away from the arcane universe of Siam’s royal court which appeared to be dimming into insignificance and extinction. He was pulled gradually into the orbit of the palace as his elder brother Ananda unexpectedly found himself first in line for the royal succession before even more unexpectedly becoming the reluctant Rama VIII. And then one momentous morning in June 1946, Ananda was found dead in his bed in the Grand Palace, shot in the head, a mystery that has never been solved, and 18-year-old Bhumibol Adulyadej was suddenly the ninth monarch of the Chakri Dynasty.

It was a position that had already been stripped of almost all of its formal powers and most of its wealth. Ananda’s death deepened doubts that the Thai monarchy would survive at all. The fortunes of the House of Chakri appeared to be at their lowest ebb. Yet over succeeding decades, against seemingly insurmountable odds - not to mention the tide of history - Bhumibol restored a central role for the palace in Thailand and won the adoration of the vast majority of his people as the beloved "Father of the Nation". In the words of journalist Paul Handley in his groundbreaking academic biography The King Never Smiles:

King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s restoration of the power and prestige of the Thai monarchy is one of the great untold stories of the 20th century....

Overnight, the happy-go-lucky, gangly, and thick-spectacled Bhumibol... became King Rama IX, holy and inviolate sovereign of a land whose language he spoke poorly, whose culture was alien to him, and whose people, compared to those of Switzerland, seemed crude and backward.

From the day of his brother’s death, the story of Bhumibol’s reign developed like a tale from mythology. After four more years in Europe studying, Bhumibol finally returned in 1950 for an opulent formal coronation. He married a vivacious blue-blooded princess, Sirikit, who would become world famous for her charm and beauty. They had four children, including one handsome boy to be heir and three daughters.

A figure of modernity in a feudal-like society stuck in the 1800s, the young king sailed, played jazz, ran his own radio station, painted expressionist oils, and frequented high-society parties. Whenever required he donned golden robes and multi-tiered crowns ... to undertake the arcane rituals and ceremonies of traditional Buddhist kingship...

At each juncture, his power and influence increased, rooted in his silent charisma and prestige.

...........

In June 2006, King Bhumibol marked 60 years on the throne of Thailand, amid an outpouring of adoration from the Thai people and an impressive show of respect from other royal families around the world. Thirteen reigning monarchs attended the celebrations in person, and 12 others sent royal representatives. The only reigning royal families not represented were those of Saudi Arabia and Nepal. The Saudi absence was due to the ill-health of the octogenarian King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz, officially at least, but relations between the two countries had been tarnished by a dispute over the unsolved theft of a famed blue diamond and other priceless gems from the Saudi royals in which Thailand’s police and powerful establishment figures were implicated. The Nepalese monarchy was still in turmoil following the 2001 massacre of King Birendra, Queen Aishwarya and many of their relatives by their son, Crown Prince Dipendra, who went on a drunken rampage through the Narayanhity Royal Palace in Kathmandu with a Heckler & Koch MP5 submachinegun and an M16 assault rifle before committing suicide. Over several days of joyous festivities, millions of Thais wore the royal colour of yellow to show their respect. Fireworks lit up the sky, and the assembled monarchs watched the unforgettable sight of a royal barge procession, with 52 sleek dragon-headed vessels rowed by liveried Thai oarsmen gliding down the Chao Phraya past the Grand Palace. An estimated one million people crowded into Bangkok’s Royal Plaza on Friday June 9 as Bhumibol gave a public address - only his third in six decades - from a palace balcony. Many millions more watched intently on television. Later that day at the auspicious time of 19:19, hundreds of thousands who had gathered around the brightly illuminated buildings of the Grand Palace lit candles in his honour. In a confidential U.S. embassy cable, American Ambassador Ralph "Skip" Boyce described the celebrations: The multi-day gala offered dramatic and often times moving evidence of the nation’s respect and adoration for its monarch... While the Thai people’s respect and reverence for the 78 year old monarch is often cited, the weekend’s celebration was a rare occasion to see - and feel - the depths of this sentiment in person. In contrast to the tens of thousands who have rallied against and in support of the Thaksin government, the King’s public address on Friday at [the] throne hall inspired an estimated one million Thai to brave the mid-day sun to listen to their "father" speak... Much of the audience had camped out since the evening before... All local television stations carried the same live feed of each event, which featured crowd shots of attendees alternately crying and smiling. Late night television shifted to cover the opening of the World Cup, but even this event was colored by the King’s celebration: a newspaper cartoon explained that most Thai people were cheering for Brazil because the Brazilians wear yellow uniforms. It was an astonishing testament to Bhumibol’s achievements in the six decades since he inherited the crown at such a perilous time for the monarchy and in such tragic circumstances.

And yet even as he basked in the adoration of his people and the respect of the world, Bhumibol was acutely aware that everything he had built during his 60 years on the throne was at risk of being reduced to ruins by mounting internal and external challenges that threatened to undermine the foundations of the Thai monarchy and destroy his legacy. The father of the nation was facing serious problems within his own divided family: Boyce refers to the celebrations in his cable as “the dysfunctional family picnic”. Bhumibol had been estranged from Queen Sirikit for two decades since she suffered a breakdown following the mysterious death of her favourite military aide. Rama IX’s son and heir, Crown Prince Maha Chakri Vajiralongkorn, was a cruel and corrupt womanizer, reviled by most Thais almost as viscerally as Bhumibol was loved. The king’s second daughter, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, was the overwhelming favourite of the Thai people to succeed her father, even though her gender and royal tradition seemed to render this impossible. As Boyce wrote in his cable: In a shot heavy with unintentional meaning on Friday, the television broadcast showed the unpopular Crown Prince reading a message of congratulations to the King, who was seated on the royal balcony above the Prince. Just visible behind the King, however, was the smiling face of Princess Sirindorn - the widely respected "intellectual heir" of the monarch - chatting with her sisters and trying to take a picture of the adoring crowd below. The physical distance between the King and his legal heir far below, and his beloved daughter just behind him, captured the internal family dynamic - and the future of the monarchy - quite nicely. Besides marital strife and an underachieving wayward son, Bhumibol was also troubled by the bitter power struggle between Thaksin and Thailand’s traditional elites, which was becoming increasingly divisive and dangerous: In his public remarks on Friday, the King thanked the assembled dignitaries and crowd for their congratulations and called upon the Thai people to show compassion, cooperate with each other, display integrity, and be reasonable. In a not-so-veiled reference to the ongoing political crisis, the King stated, "unity is the basis for all Thai to help preserve and bring prosperity to the country". Prime Minister Thaksin had been fighting a rearguard action for months against a determined effort by Thai monarchists to oust him. His role in the celebrations was deeply ambivalent, Boyce noted: Prime Minister Thaksin was front and center for much of the festivities: greeting foreign guests, and reading a congratulatory message for the King on behalf of the caretaker government. In an unfortunate bit of timing, the television camera covering the opening ceremony on Friday panned on the PM just as he was checking his watch. Aside from this minor gaffe - not mentioned in the newspapers, yet - the PM’s personal perspective on the celebration remains unclear... Thaksin recently told the Ambassador that his own popularity in the countryside is seen by the palace as threatening to the King’s popular standing. After this weekend’s massive, unprecedented display of public adoration for the monarch, however, one hopes that Thaksin has a firm enough grasp of reality to reconsider this idea.

Within months of the Diamond Jubilee celebrations, Thailand’s smouldering tensions exploded. In September 2006 Thaksin was deposed by a military coup - the 18th attempted by Thailand’s military since the country began its halting and bloody flirtation with democracy in 1932. The generals who ordered their tanks onto Bangkok’s streets believed they were defending the monarchy and insisted they were acting in support of democracy against an increasingly authoritarian and mercurial prime minister who had co-opted most of the country’s key institutions and subverted the rule of law. Yet the elderly men who took charge of Thailand after the coup were completely unprepared for the challenges of running a 21st century economy and totally bewildered when it came to trying to counter the machinations of a mediasavvy telecommunications tycoon with deep pockets and a determination to get even, whatever the cost. A coup designed to crush support for Thaksin and end his influence over Thai politics forever was an abject failure. It only succeeded in wrenching an already divided country even further apart. The highstakes struggle between Thailand’s most powerful figures spilled onto the streets of Bangkok, where mass protests and civil disobedience by the royalist "Yellow Shirt" followers of the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the broadly pro-Thaksin "Red Shirts" of the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) erupted repeatedly into violent clashes and destructive efforts to sabotage the very functioning of the Thai state. By the autumn of 2009, when Bhumibol was admitted to Siriraj Hospital, the country was mired deep in an intractable social and political crisis with no apparent way out.. As the end of his life approached, instead of looking back with pride over his incredible achievements, Bhumibol was fretting over fears that everything he had fought to achieve during his extraordinary reign was in danger of turning into dust.

Of all the world’s countries, Thailand is among those for which the publication of the U.S. embassy cables could have potentially the most profound impact. All nations have their secrets and lies. There is always a gulf between the narrative constructed by those in power, and the real story. But the dissonance between Thailand’s official ideology and the reality is particularly stark and troubling. Suthep Thaugsuban, Thailand’s deputy prime minister, blithely claimed in December 2010 that the cables would have no impact on the country: We don’t have any secrets... What happens in Thailand, we tell the media and the people. His comments could scarcely be further from the truth. Thailand is a nation of secrets, and most of the biggest secrets are those involving the Thai monarchy. The palace is at the centre of an idealized narrative of the Thai nation and of what it means to be Thai, which depicts the country as a uniquely blessed kingdom in which nobody questions the established order. Thais are well aware that the truth is very different - they could hardly be otherwise, following the violent political crisis that has engulfed their country - and yet many continue to suspend their disbelief and, at least publicly, to profess their faith in the official myths. Most feel unable to voice the truth, due partly to immense social pressure in a society where to question the official story is to be regarded as "un-Thai", and partly to some of the strictest defamation laws in the world. At the heart of the legal structure protecting the official myth is the lèse majesté law. Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code states: "Whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years."

A law originally intended to shield the monarchy from insults and slander has become something far more: it is increasingly used to prevent any questioning of Thailand’s established social and political order. As historian David Streckfuss says in the foremost academic work on the subject, Truth on Trial in Thailand: Defamation, Treason, and Lèse Majesté: "Never has such an archaic law held such sway over a ’modern’ society (except perhaps ’Muslim’ theocracies like Afghanistan under the Taliban)": Thailand’s use of the lèse majesté law has become unique in the world and its elaboration and justifications have become an art. The law’s defenders claim that Thailand’s love and reverence for its king is incomparable. Its critics say the law has become the foremost threat to freedom of expression. Barely hidden beneath the surface of growing debate around the law and its use are the most basic issues defining the relationship between those in power and the governed: equality before the law, rights and liberties, the source of sovereign power, and even the system of government of the polity - whether Thailand is to be primarily a constitutional monarchy, a democratic system of governance with the king as head of state, or a democracy. Most Thais remain unaware of the full story of how Bhumibol restored the power and prestige of the monarchy over the past half century. Handley’s book The King Never Smiles is banned in Thailand - as is Handley himself - because he violated the taboo that forbids a critical look at the role of the palace in Thailand’s modern history. As he writes in the introduction: Any journalist or academic who takes an interest in Thailand soon learns that one topic is offlimits: the modern monarchy. One is told variably that there is nothing more to say than the official palace accounts; that such matters are internal; that the subject is too sensitive and complex for palace outsiders to handle; or simply that it is dangerous, and one risks expulsion or jail for lèse majesté. Most people give in to these explanations with little argument. It is easy to do: nearly every Thai one meets expresses unquestioning praise for the king, or at least equivocates to the point of suggesting that there really is not much to be said: the history that is in the open is the whole of it. Palace insiders sometimes concede that there is indeed more to the story, but then demur to say that only real insiders, only Thais within the inner royal circle, can comprehend the mysteries of the king’s reign. The subject, then, hardly seems worth the trouble to dig into, and so as even the most curious succumb to Thailand’s charm and King Bhumibol’s carefully crafted image, the palace remains an enigma. The result, however, is a crucial gap in modern Thai history and political analysis. Thongchai Winichakul, a history professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and visiting fellow at the National University of Singapore, discussed the chilling effect of the lèse majesté law in his 2008 paper Toppling Democracy: The current generation of Thais mostly grew up after the Second World War when they no longer lived with the memories and experiences of the 1932 revolution. Instead they have lived through military rule and the struggle against it, and through the time when the monarchy has been elevated to a sacred and inviolable status. The role of the monarch and the ‘‘network monarchy’’ in past or present politics are ... beyond public discussion, due to the lèse majesté law that would penalise anybody who defames the monarch with up to fifteen years in jail. The lack of conceptualised narratives that explain how the monarchy remains a critical element in Thai democratisation further contributes to overlooking the political role of the monarchy. Discussion of the reality among Thais is relegated to private conversations or oblique references using coded imagery and parables. The truth about the palace’s enormously influential role in Thai politics and economics cannot be uttered openly in public. As Streckfuss says: The lèse majesté law shields this overwhelming, inescapable presence in Thai society, politics and the economy. As a result, the operation of the lèse majesté law in Thailand creates a black hole of silence in the center of the Thai body politic. Political and social discourse is relegated to the fringes as whisperings and innuendo.

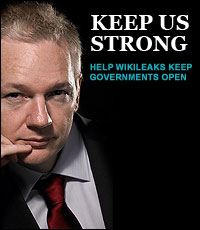

The WikiLeaks Cablegate database contains 2,930 cables from the U.S. embassy in Bangkok, 71 of them secret, and a further 239 from the U.S. embassy in Chiang Mai, 17 secret, plus dozens more from other U.S. embassies that also discuss Thailand. Only a handful of have been published so far. The cables begin in late 2004, when Thaksin was at the height of his political ascendancy, and end in early 2010 when Thaksin was in exile, current Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva was in power, and Thailand was about to enter the most tragic phase of its crisis so far. Most were written by Ralph "Skip" Boyce, ambassador from 2004 to 2007, and Eric G. John, ambassador from 2007 until 2010. One reason above all makes the leaked U.S. embassy documents invaluable for an understanding of modern Thailand: unlike almost all journalistic, academic and public discourse on the country, they were written without explicit and extensive self-censorship about the absolutely pivotal role played by the monarchy in Thai political developments throughout the country’s modern history. Explaining Thai politics without reference to the role of the palace is like trying to tell the story of the Titanic without making any mention of the ship. Some brave Thais in the media and academia make a valiant effort, through the use of tortured euphemisms and oblique hints, as Pravit Rojanaphruk, one of the country’s most outstanding journalists, wrote in a June 2011 column: The "invisible hand", "special power", "irresistible force", all these words have been mentioned frequently lately by people, politicians and the mass media when discussing Thai politics, the upcoming general election and what may follow. These expressions are used as a substitute for an alleged unspeakable and unconstitutional force in Thai politics, to make the otherwise incomplete stories about politics and its manipulation slightly more comprehensible.

The leaked U.S. cables do not have to resort to enigmatic innuendo about hidden hands and spooky inexplicable influences. They were written by American diplomats doing their best to explain events in Thailand to the State Department in Washington. They were intended to be secret, made public only when the events they described were distant history and the people involved were long dead. Those who wrote them did not have to fear the threat of social ostracism or lengthy jail sentences if they simply tried to give a clear explanation of the most important issues facing the people of Thailand at a momentous time in their history at the start of the 21st century. The account they give of Thailand’s ongoing political crisis may not always be correct: like everybody else struggling to unravel the truth, senior U.S. diplomats had to rely on sources who were by no means always honest and who often gave a partial or even deliberately misleading picture. John explicitly concedes this point in one of the most remarkable of all the cables, from November 2009, entitled "CIRCLES OF INFLUENCE INSIDE THE INSTITUTION OF THE MONARCHY IN KING BHUMIBOL’S TWILIGHT": The Thai institution of monarchy remains an opaque institution, full truths about which are difficult to fix with any certainty... We offer this "royal primer" mindful of the opaque nature of the institution, the difficulty in establishing absolute truths about public yet very remote royal figures, and the inherent biases of inside players, even those we have known for years (several of whom recently repeated a Thai aphorism about the institution: "those who know aren’t talking, and those who are talking aren’t in the know"). The cables also reflect the biases of their authors: like many Western observers of Thailand, Boyce and John were always uneasy with Thaksin’s demagoguery and corruption, and were much more comfortable dealing with the refined, patrician, British-born and educated Abhisit, described by John as "a photogenic, eloquent 44-year old Oxford graduate who generally has progressive instincts and says the right things about basic freedoms, social inequities, policy towards Burma, and how to address the troubled deep south”. John seems to have only realized rather late that Abhisit’s instincts may not have been as progressive as they appeared, and that while he may say the right things, that does not mean that he does them. No other country has been so inextricably involved with Thailand over the past century as the United States, and this adds even more value to what the cables have to say. America’s influence has had a transformative impact on Thailand - and on the life and reign of U.S.-born King Rama IX. And just like the palace’s critical but secret role in shaping Thailand’s destiny, the central part played by the United States is often obscured and denied. As Christine Gray wrote in her remarkable 1986 PhD dissertation, Thailand: The Soteriological State in the 1970s: Any study of contemporary Thai society must account for the U.S. influence on that polity and the mutual denial of that influence. Thailand’s relationship with the United States is complex, heavily disguised and, in many instances, actively denied by the leaders of both countries...

In many cases, it is difficult if not impossible to determine the extent of American influence in Thailand. Thailand is a nation of secrets: of secret bombings and air bases during the Vietnam War, of secret military pacts and aid agreements, of secret business transactions and secret ownership of businesses and joint venture corporations. This is precisely the point; the American presence has taken on powerful cosmological, religious and even mythic overtones. The American influence on the Thai economy and polity has become a symbol of uncertainty, of men’s inability to know the truth. The end of the Cold War marked a change in the relationship, but it remains fundamentally important, particularly given Thailand’s role in the so-called “War on Terror" and America’s geopolitical rivalry with a rising China. In multiple cables written for visiting high-level officials, John wrote that "Thailand’s strategic importance to the U.S. cannot be overstated". The country hosted one of the CIA’s infamous “black sites” where al Qaeda prisoners were tortured: vociferously denied, of course, by the Thais, and never acknowledged by the Americans. The leaked cables provide a coherent and insightful account of the complexities of Thailand’s crisis by respected senior U.S. diplomats who consider the kingdom a crucial strategic partner, who have unparalleled access to most of the key players, and who did not censor the monumental role of the monarchy out of their analysis. As such, they revolutionize the study of 21st century Thailand. But their importance goes further. The cables do not merely illuminate Thailand’s history - they are also likely to have a profound impact on its future. The official culture of secrecy that has criminalized public acknowledgement of truth among Thais and prevented academic and journalistic study of fundamental issues affecting the country has been irretrievably breached. The genie cannot now be put back into the bottle. Some underwhelmed critics of the leaking of Cablegate documents have dismissed them as containing few genuine revelations - in general, they have largely tended to confirm what everybody suspected all along. And this is to some extent true of the cables on Thailand. There are no bombshells that will stun Thais or foreign experts on Thailand who are already aware - at least privately - of the story that the cables tell. But this is missing the point. As Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has argued in a brilliant essay on WikiLeaks: The only surprising thing about the WikiLeaks revelations is that they contain no surprises. Didn’t we learn exactly what we expected to learn? The real disturbance was at the level of appearances: we can no longer pretend we don’t know what everyone knows we know. This is the paradox of public space: even if everyone knows an unpleasant fact, saying it in public changes everything. Hans Christian Andersen made the same point in his parable The Emperor’s New Clothes. Even if most people privately suspect the truth, putting it in the public domain makes it impossible to sustain official narratives that depend on a refusal to acknowledge the reality.

For that reason, the cables may, finally, force Thailand to confront some uncomfortable facts about its past, its present, and its future.

Bhumibol has remained in Siriraj to this day. And the king still suffers restless nights, according his youngest daughter Princess Chulabhorn Walailak in an extraordinary interview with popular talk show host Vuthithorn “Woody” Milintachinda, broadcast in two parts in April. Amid scenes of an emotional Woody prostrating himself on the ground, eagerly sharing a cupcake fed to the princess’s pet dog, and frequently bursting into tears, Chulabhorn told him: HM goes to sleep very late. Sometimes he cannot sleep. Sometimes he sleeps a little. Sometimes when there are problems, he would follow them up, like floods, for example, concerned about the hardship of the people. He would order [officials] to send bags of emergency supplies to the people. When he sees on TV where are floods, where it is hot, or where people have been injured, he will give help without telling anyone. He does good without being seen indeed. If I were not his child, I’d never know this. His continued hospitalization since September 2009, even when his health had seemed to be on the mend, has troubled Thais and baffled foreign observers. As Eric John wrote in February last year: The real question at this stage remains: why does he continue to be hospitalized? The stated rationale - to build up his physical strength and endurance - could be accomplished in a palace, either in Bangkok or his preferred seaside residence in Hua Hin. Some will suspect other motives, but what those might be remain unclear. [10BANGKOK287] More than a year later, Bhumibol’s behaviour seems even more of a mystery. During the king’s seclusion in Siriraj, the malady afflicting the nation has only worsened. In March 2010, many thousands of Red Shirt protesters began congregating in Bangkok for a series of mass rallies against the government of Prime Minister Abhisit. Over two tragic months in April and May, as the military moved in to try to crush the protest, 91 people were killed and more than 1,800 wounded in a series of violent clashes between Thai troops, Red Shirts and shadowy groups of armed men known as "Black Shirts" or "Ronin warriors" with unclear affiliation to Thaksin and the protest leaders. For weeks the Red Shirts occupied an area of five star hotels and luxury malls in the centre of the capital, a few miles east of Bhumibol’s riverside hospital. When soldiers finally stormed the barricades around the Red encampment, on May 19, dozens of buildings in Bangkok were set ablaze in an apparently well-planned wave of arson attacks. The months that followed saw a determined crackdown by Thailand’s resurgent military and the Abhisit administration. A state of emergency was imposed in several areas,. Most Red Shirt leaders were imprisoned. Community radio stations in rural areas where Red support is strong were shut down. The millions of rural and urban poor who form the main support base for the Red Shirt movement were left seething with anger and a bitter sense of injustice.

Another element of the crackdown was increasing use of the lèse majesté and computer crimes laws to stifle dissent. Respected journalists and academics have been among those targeted. In late May, Lerpong Wichaicommart, a 54-year-old Thai man with U.S. citizenship who also calls himself Joe Gordon, was arrested in Thailand on charges of using the internet to insult the monarchy that could carry a sentence of up to 22 years. Among his alleged offences was providing a link on his website to a digital version of The King Never Smiles. In such a climate, it became clear that the article I was writing on Thailand, based on the full set of more than 3,000 leaked U.S. embassy documents relevant to the country, could never be published by Reuters. Even though U.S. diplomatic cables were the key source material, and they were always going to eventually end up in the public domain after WikiLeaks acquired them, just linking to them and discussing their content as this article does will be regarded by many in Thailand as a highly provocative act. Quite clearly it represents lèse majesté on an epic scale. Reuters has hundreds of staff in Thailand, and there were concerns they could be put at risk. Like all major foreign media organizations, the company has had to self-censor its reporting from Thailand for years, to protect its staff and the revenues it earns in Thailand. The U.S. cables were just too risky to run. It was an understandable decision. But for me, there could be no turning back. From the day I first arrived in Bangkok 11 years ago as deputy bureau chief for Reuters, I was - like most visitors before me over the centuries - beguiled by the luminous beauty and vibrancy of Thai culture, and moved and inspired by the graciousness, charm and warmth of most Thai people. No other place in the world means more to me, and nowhere else has broken my heart more often. It just became impossible to ignore all the everyday horror and human misery that are allowed to flourish in Thailand alongside so much to cherish and admire. And it troubled me that so many Thais seemed to have lost faith in their ability to solve the problems their country faces, and had decided to just pretend the problems didn’t exist at all. Thailand needs to escape the wretched cycle of corruption, conspiracies and coups that has blighted its modern history. A first step is to clearly acknowledge what is happening in Thailand today. Thailand’s people deserve to know the truth, and they deserve to be allowed to express what they believe, instead of facing jail or exile for simply saying things that cannot be denied. As Pravit says, “like a vampire fearing the scrutiny of sunlight, Thai politics can never be comprehensible or democratic without trying to make visible the invisible hand”: The hand (he or she, there could be more than one invisible hand), operates in the shadow because it cannot bear the scrutiny, the transparency and accountability of a democratic society. It also apparently does not believe the majority of voters should be able to elect their own representatives and determine the future course of Thai society. Politics in Thailand has become more and more like a badly acted television drama series. The actors all know that the lines they are speaking and the roles they are playing while the cameras are rolling are not real: the reality is quite different. The audience knows it too. When we watch a television melodrama, of course, we don’t start complaining that what we are watching is fake. We allow ourselves to imagine it is real, to enjoy the show. Thailand’s tragedy is that people have come to view the dismal farce acted out by their politicians, generals, bureaucrats and business tycoons in the same way: everybody knows it’s all fake, but everybody feels it wouldn’t be polite to interrupt the theatrics by saying so. With the greatest of respect, it’s time to say the show is over. Thailand needs to start dealing with reality. Especially now, when the whole country is convulsed by anger and pain and anxiety, and when so many dark clouds are gathering on the horizon. Everybody knows that a storm is coming. The only question is how much time is left before it hits. What happens then will fundamentally define what kind of country Thailand becomes in the 21st century. You don’t get any shelter from a storm just by closing your eyes and refusing to look at it. When I realized I would not be able to say what needs to be said about Thailand as a Reuters journalist, I began making copies of all the U.S. cables relating to the country over a few fraught sleepless nights of frenetic cutting-and-pasting and excessive amounts of Krating Daeng. Technology has made the theft of secret information much easier than it used to be: an eccentric Thai writer and publisher called K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon had a much more difficult time 130 years ago when he wanted to share the wealth of accumulated historical wisdom contained within the manuscripts held in the Royal Scribes’ library in the Grand Palace. He saw his chance when the library was under renovation and the manuscripts taken out of the palace and entrusted to the care of Prince Bodinphaisansophon, head of the Department of Royal Scribes. Craig Reynolds tells the story in Seditious Histories: Contesting Thai and Southeast Asian Pasts: The accessibility of these manuscripts to Kulap sparked his curiosity, and out of his love for old writings, he paid daily visits to admire the most ancient books in the kingdom. Naturally, he desired copies for himself, his passion for old books guiding him around any obstruction. According to Prince Damrong’s account of the episode, based on conversations with Kulap’s accomplices, he circumvented the prohibition on public access to such documents by persuading Prince Bodin to lend the texts overnight one at a time. With a manuscript in his possession, Kulap then rowed across the river to the Thonburi bank to the famous monastery, Wat Arun or Wat Claeng. There, in the portico of the monastery, Kulap spread out the accordion-pleated text its entire length, and members of the Royal Pages Bodyguard Regiment, hired by Kulap to assist in this venture, were then each assigned a section of the manuscript. In assembly-line fashion, they managed to complete the transcription within the allotted time. Kulap then rowed back across the river to return the original, with the prince apparently none the wiser. On June 3, 2011, I resigned from Reuters after a 17-year career so that I could make this article freely available to all those who wish to read it. Reuters was explicitly opposed to my actions and sought to prevent me writing it while I was employed there. They have also informed me several times of the potential consequences of making unauthorized use of material that came into my possession through my work as a Reuters journalist. I have chosen to disregard those warnings, but it is important to make clear that Reuters made every reasonable effort to stop me publishing this story, and some frankly rather unreasonable efforts too. Responsibility for the content and the consequences of my article is mine, and mine alone. Besides having to leave a job I loved with a company I had believed in, it also seems likely that I can never visit Thailand again. That feels unbearably sad. But it would have been infinitely sadder to have just accepted defeat and given up trying to write something honest about Thailand. My duty as a journalist, and as a human being, is to at least try to do better than that. What follows is a rough first draft of the truth.

I. “A WATERSHED EVENT IN THAI HISTORY”

One inescapable and traumatizing fact haunts 21st century Thailand, and not even the country’s most potent myths have the power to tame it: Bhumibol Adulyadej, the beloved Rama IX, is approaching the end of his life. Frail and hospitalized, he is already just a shadow of his former self. His designated successor, Crown Prince Maha Chakri Vajiralongkorn, is widely despised and feared. Whether or not the prince becomes Rama X, the royal succession will be a time of profound national anxiety and uncertainty far more shattering and painful even than the tragic events of the past five years of worsening social and political conflict. The looming change in monarch and the prolonged political crisis gripping Thailand are - of course inextricably intertwined. A large number of parallel conflicts are being fought at all levels of Thai society, in the knowledge that Bhumibol’s death will be a game-changing event that will fundamentally alter longstanding power relationships among key individuals and institutions, and may also totally rewrite the rules of the game. Ahead of the succession, the leading players are fighting to position themselves for of the inevitable paradigm shift. Professor Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University’s faculty of political science, describes the crisis beautifully in Thailand Since the Coup, published in the Journal of Democracy in 2008: The setting sun of the King’s long reign is the background against which the battle of attrition for Thailand’s soul is taking place. In this twilight struggle are locked opposing webs of partisans and vested interests both for and against what Thaksin has done to Thailand. The old establishment confronts the popular demands and expectations that the age of globalization has wrought, and strains to find ways to render the new voices irrelevant.

When very important U.S. officials come to town, American ambassadors around the world prepare for them a confidential "scenesetter", a concise briefing to read during their flight, about the country in which they are about to arrive. In July 2009, it was the task of Eric G. John, the American ambassador in Bangkok and a former deputy assistant secretary of state for Southeast Asia, to write a scenesetter for a particularly important visitor: his boss, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the woman in charge of the foreign policy of the most powerful nation in the world. Here is what he wrote about the "troubled kingdom" of Thailand in cable 09BANGKOK1662, "THAILAND SCENESETTER FOR SECRETARY CLINTON’S JULY 21-23 VISIT": Madam Secretary: You will arrive July 21 in a Kingdom of Thailand divided politically and focused inward, uncertain about the country’s future after revered but ailing 81 year old King Bhumibol eventually passes. …

The past year has been a turbulent one in Thailand. Court decisions forced two Prime Ministers from office, and twice the normal patterns of political life took a back seat to disruptive protests in the streets. The yellow-shirted People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) occupied Government House from August to December 2008, shutting down Bangkok’s airports for eight days in late November, to protest governments affiliated with ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The red-shirted United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), followers of Thaksin, disrupted a regional Asian Summit and sparked riots in Bangkok in mid-April after Thaksin, now a fugitive abroad in the wake of an abuse of power conviction, called for a revolution to bring him home. While both yellow and red try to lay exclusive claim to the mantle of democracy, neither is truly democratic in intent or tactics. The current PM, Abhisit Vejjajiva... is beset with a fractious coalition, with partners more interested in self-enrichment than good governance, as well as a resurgent post-2006 coup military not interested in political compromises in the deep south or reducing its profile, at least as long as uncertainty over a looming royal succession crisis remains to be resolved. While Thailand in 2009 has been more stable than in 2008, mid-April red riots aside, it is the calm in the eye of a storm. Few observers believe that the deep political and social divides can be bridged until after King Bhumibol passes and Thailand’s tectonic plates shift. Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn neither commands the respect nor displays the charisma of his beloved father, who greatly expanded the prestige and influence of the monarchy during his 62 year reign. Some question whether Vajiralongkorn will be crowned King, as Bhumibol desires. Nearly everyone expects the monarchy to shrink and change in function after succession. How much will change is open to question, with many institutions, figures, and political forces positioning for influence, not only over redefining the institution of monarchy but, equally fundamentally, what it means to be Thai. It is a heady time for observers of the Thai scene, a frightening one for normal Thai. The political crisis that has riven Thailand since the start of Thaksin’s struggle with the establishment can only be understood in this context, as John explains in cable 09BANGKOK2967: Bhumibol’s eventual passing will be a watershed event in Thai history. It likely will unleash changes in institutional arrangements in Thailand, affecting the size and role of the monarchy, its relationship to the elected government and the military, and the roles of both of the latter, unmatched since the 1932 transition from absolute to constitutional monarchy, which nevertheless retained the monarchy at the core of Thai national identity. The twilight of Rama IX’s reign is casting long shadows across the political landscape: It is hard to underestimate the political impact of the uncertainty surrounding the inevitable succession crisis which will be touched off once King Bhumibol passes. Over the past year, nearly every politician and analyst, when speaking privately and candidly, regardless of political affiliation or colored perspective, has identified succession as the principal political challenge facing Thailand today, much more important than normal political issues of coalition management or competition for power, which clearly do factor into the mix of political dynamics... It is entirely possible King Bhumibol will return to his Hua Hin seaside palace several hours south of Bangkok in the coming days and live quietly for many years - postponing the day of reckoning and change that will inevitably come. In the meantime, the bustle of normal politics and changing societal attitudes will continue apace, while Thais keep a wary eye on the health of their ailing King. [09BANGKOK2488] Fear about the succession transfixes many Thais at all levels of society, and evidence of it can be seen everywhere. Duncan McCargo, professor of Southeast Asian politics at the University of Leeds, begins his study Thailand: State of Anxiety in Southeast Asian Affairs in 2008 with a reference to an obsession that swept the nation for magical amulets originally created by policeman in the southern town of Nakhon Si Thammarat. They became so wildly popular that in April 2007 a woman was killed in a stampede at the temple where they were made, and a crime wave spread worsening havoc through the town as Thais unable or unwilling to buy the amulets decided to try stealing them instead. The chaos prompted Thailand’s supreme patriarch - the most senior Buddhist monk in the kingdom - to declare he would no longer provide some of the sacred ingredients, such as incense ash from his temple, used in the production of the lucky amulets. "Today, Thai people are without hope … there is no certainty in their lives." This statement came not from one of Thailand’s many academics or social critics, but from a popular young entertainer, Patcharasri "Kalamare" Benjamas. She was writing about the national anxiety epitomized by the extraordinary cult of Jatukham Ramathep amulets which seized Thailand in late 2006 and the first half of 2007. Deeply uneasy about the economy, politics, and the royal succession, Thais bought tens of millions of these much-hyped amulets to protect them from adversity.... The fevered collective enthusiasm for monarchy seen during 2006 and 2007 had a darker downside, testifying to growing national anxiety about the royal succession... The inability of the palace to address public anxiety about the succession threatened to undermine the glory of the Ninth Reign. [McCargo, Thailand: State of Anxiety] McCargo has convincingly argued that the gruesome mutation that afflicted the Yellow Shirt movement of the People’s Alliance for Democracy is also a symptom of the panic stalking Thailand as the Bhumibol era comes to an end. The Yellow Shirts were initially a broad-based and relatively good-humoured alliance from across the ideological and political spectrum that drew together royalists and liberals, radical students and middle-class aunties, progressive activists and patrician establishment patriarchs, united in opposition to the increasingly baleful influence of Thaksin Shinawatra; over the years they morphed into a proto-fascist mob of hateful extremists addicted to the bloodcurdling rhetoric of rabble- rousing demagogues. The Yellow Shirts proclaim their undying love for the king, but it is the flipside of that love that has transformed them into a baying apocalyptic death cult: they are utterly petrified about what will happen once Rama IX is gone. Thailand was firmly in the grip of “late reign” national anxiety, which formed the basic explanation for the otherwise illegible performances and processions of the PAD... As time went on, the PAD became captives of their own rhetoric, unable to converse with others, let alone back down or make compromises. Rather than seek to build broad support for their ideas, core leaders made vitriolic speeches... in which they denounced anyone critical of, or unsympathetic, to their actions. Such megaphone posturing served to alienate potential supporters, and to strengthen the PAD’s dangerous sense of themselves as an in-group of truthtellers and savants, whose nationalist loyalties were not properly appreciated or understood. This self-presentation had distinctly cultic overtones... [McCargo, Thai Politics as Reality TV] Another stark indication of anxiety about the succession - due to the uncertainty and additional risk it will inject into investment decisions - was the collapse in the Thai stock market in October 2009 on rumours that Bhumibol’s health had taken a turn for the worse: As widely reported in the local and international press, rumors of the King Bhumibol’s ill health drove the Thai stock market into a frenzy for two straight days this week. Combined losses over the two days amounted nearly $13 billion... The market jitters and selling frenzy on the trading floor demonstrates just how sensitive investor confidence in Thailand is to news about the King’s health. This volatility creates a wealth of opportunities for mischief in the market, particularly for profit-seekers and bargain-hunters. The veracity of rumors is very difficult to track down, but their impact on the market, true or not, is clear. [09BANGKOK2656] And yet Thailand claims to be a constitutional monarchy, in which the king does not interfere in politics. The extent of the fear and turmoil roiling Thailand in the final years of Bhumibol’s reign can be baffling for foreign observers. In Britain, Queen Elizabeth II is fairly widely respected even among those who are indifferent or opposed to the monarchy, and few people are greatly enthused about the prospect of Prince Charles becoming king, but the country is hardly convulsed by frantic worry about the succession. Quite clearly, Bhumibol is no ordinary constitutional monarch. And making sense of Thailand’s trauma requires some understanding of what the monarchy means to Thais, and in particular how Bhumibol came to hold such a special place in their hearts.

Bhumibol’s ascent to the throne of Thailand was so improbable that it would strain credibility in a work of fiction. His mother Sangwal was born in 1900 to impoverished parents, a Thai-Chinese father and a Thai mother, in Nonthaburi near Bangkok. By the time she was 10 both her parents and an elder sister and brother had all died, leaving her an orphan with one younger brother. Through some fortunate family connections she moved into the outer orbit of the royal court, and after an accident with a sewing needle she was sent to stay in the home of the palace surgeon who encouraged her to become a nurse. At the age of just 13 she enrolled at Siriraj Hospital’s School for Midwifery and Nursing. She met Bhumibol’s father, Mahidol Adulyadej - 69th of the 77 children of Rama V, King Chulalongkorn - in Boston in 1918 after winning a scholarship to further her nursing studies in the United States. If anybody had expected Mahidol to get anywhere near the pinnacle of the royal line of succession, his marriage to a ThaiChinese commoner would never have been approved. But he was far down the list. Bhumibol was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1927, the couple’s third child after a daughter, Galyani Vadhana, and a son, Ananda Mahidol. His name means "Strength of the Land, Incomparable Power".

By the time Bhumibol was born, his father had been catapulted into contention for the throne, after several other claimants died young and childless. But Mahidol was studying medicine and wanted to be a doctor; he had no interest in becoming king. In December 1928, the family returned to Siam. Mahidol hoped to practise as a doctor in Bangkok, but palace law decreed that his royal status meant he could not touch any part of a patient’s body apart from the head. Trying to escape restrictions he considered ridiculous, he went to work at the American Presbyterian Hospital in the northern town of Chiang Mai. Shortly afterwards the chronic kidney problems he had suffered all his adult life flared up again. He died in September 1929 in Bangkok, aged 37. This put the young Ananda first in line for the throne, with Bhumibol next. Even then, it seemed very unlikely that Bhumibol would ever rule Thailand. King Prajadhipok, Rama VII, was still a young man, and there were doubts about how long long the monarchy would last in a modernising Thailand and a changing world in which many royal dynasties were being swept from power. Sure enough, in 1932, a group of military officers and bureaucrats overthrew the absolute monarchy in Siam. In the political ferment, Sangwal took her sons to Europe, where they set up home in Switzerland.

After trying and failing to claw back some of the royal powers stripped from him, Prajadhipok abdicated the throne in 1935, declining to name a successor. The government named Ananda Mahidol, nine years old and living in Lausanne, as King Rama XIII. Siam’s new king and his brother remained in Switzerland, far from the rituals and intrigues of the royal court, apart from a two-month visit in 1938/39. After the end of World War II, during which Siam had been occupied by the Japanese, they visited again, arriving on December 5, 1945, in a country they barely knew. It was Bhumibol’s 18th birthday; Ananda was 20, and according to many contemporary accounts, gauche, painfully shy and ambivalent about being king: Louis Mountbatten, the British commander in Southeast Asia, described him as "a frightened, short-sighted boy, his sloping shoulders and thin chest behung with gorgeous diamond-studded decorations, altogether a pathetic and lonely figure". There is no shortage of sources on Bhumibol’s life, but finding accurate accounts is difficult. Most of what has been written is hagiographic and of limited reliability; a small proportion is vitriolic and even more unreliable. Two full-length book biographies by foreign authors have been published. Paul Handley’s The King Never Smiles is a pioneering academic work, meticulously researched and infused with its author’s deep understanding of Thailand after years working as a journalist in the country. It is banned in Thailand. William Stevenson’s The Revolutionary King is riddled with factual errors and its claim to be a serious work of history has been met with derision (its subtitle - The True-Life Sequel to The King and I - hardly helps) but the book is nevertheless extremely valuable for one key reason: Bhumibol gave Stevenson unprecedented access, personally meeting with and talking to him several times over a period of six years. Whatever Stevenson’s shortcomings as a historian and writer, and despite the fact he may well have exaggerated his closeness to Bumibol, many of the tales and messages the book conveys are likely to have come directly from the king and those in his inner circle. Leading Thai officials went to extraordinary lengths to try to prevent the publication of Handley’s biography, and the book is frequently denounced in tones of horror and outrage by Thai officials. Stevenson’s book is a highly sympathetic romanticised portrait of Bhumibol that only caused outrage among historians; it is not sold in Thailand mainly because it depicts Bhumibol in a way that a Western audience would find reasonable but that would startle and baffle many Thais. Just to give one example, Stevenson repeatedly refers to Rama IX using his Thai nickname Lek, which means “little”; for Thais, who if they ever meet Bhumibol have to address him using a special archaic language called rajasap, such a thing is quite simply unthinkable.

Handley notes in the preface to The King Never Smiles that his book: is in no way meant to be the definitive version of [Bhumibol’s] story. Such a version awaits the day internal palace and government records regarding the monarchy are open to public scrutiny. Even then, some of the most pivotal moments of Bhumibol’s life are likely to remain forever shrouded in mystery. None more so than the tragic incident that propelled him onto the throne. On June 9, 1946, at 9:20 in the morning, King Ananda was found dead in his bed in the Grand Palace, lying flat on his back with a pistol beside his left hand and a bullet hole above his left eye. The mystery of his death has never been solved. Even the simple question of whether Rama VIII killed himself - either in a deliberate suicide or by accident - or whether somebody shot him remains unresolved. The Devil’s Discus, a book-length investigation by South African writer and historian Rayne Kruger, concluded that the most likely explanation was that Ananda, depressed, overwhelmed, and lovelorn over Marylene Ferrari, the Swiss girl he had left behind in Lausanne, committed suicide. However, British pathologist Keith Simpson, asked to give his opinion by Thai officials who came to see him in London and set out all the available evidence, concluded it was extremely unlikely that Ananda had shot himself. If Ananda was killed, it remains unknown who pulled the trigger. Royalists accused Pridi of being behind Ananda’s assassination and he was eventually driven into exile; after a tortuous legal process in which several defence lawyers and defence witnesses were murdered, three men - Ananda’s secretary and two pages - were executed in February 1955 for conspiring to murder the king. Yet there is no credible evidence linking any of them to his death. Stevenson’s The Revolutionary King suggests Ananda was killed by Masanobu Tsuji, a notorious Japanese spy who is portrayed as a figure of ultimate evil, masterminding mayhem and intrigue all over Asia. But it offers no genuine evidence in support of the theory, and in fact plentiful documentary sources suggest Tsuji was nowhere near Bangkok when Ananda was shot. The bizarre final chapter in the book appears to imply that even Stevenson - and Bhumibol - are doubtful about the theory.

The possibility that Bhumibol shot his brother - probably by accident - was regarded as the most likely scenario by many senior Thai officials and foreign diplomats at the time. The common view was that the truth had then been suppressed to prevent Thailand sinking deeper into turmoil. Stevenson writes that Mountbatten sent an ill-informed letter to King George VI that said “King Bhumibol shot his brother to obtain the crown”; as a result, the British king refused to receive Bhumibol, declaring “Buckingham Palace does not host murderers.” It is also widely reported that during the early years of Rama IX’s reign, on several occasions the generals locked in a power struggle with the throne used the threat of publicly revealing evidence - either real or fabricated - that the king had killed his brother, in an effort to force Bhumibol to comply with their wishes. But if there was ever any genuine evidence that Bhumibol was responsible, it has never emerged. In August 1946, amid widespread concerns that Bhumibol’s life was also in danger, the young king left Thailand to return to Lausanne. He was away from his homeland for almost four years. During his absence, the generals running the country tried to strip the throne of even more of its influence and establish themselves as Thailand’s unquestioned rulers, while a coterie of princes fought to preserve the powers of the palace. Bhumibol went back to his studies in Switzerland. The axle around which this whole cosmic wheel spun, meanwhile, was ensconced in Lausanne, Switzerland, maybe pondering his schizophrenic life. One persona was a European university student caught up in the postwar reconstruction zeitgeist. The other, less familiar identity was the sacral dhammaraja king of Thailand, turgid, conservative, confined by an entourage of elderly men who emphasized only the old... His personalized studies left him much free time to travel, play his music, and socialize. He frequently drove himself to Paris to go shopping and pass nights in smoky jazz clubs. He helped his car-racing uncle Prince Birabongs in the pits at the Grand Prix des Nations in Geneva, and in August 1948, during a motor tour of northern Europe, he watched Birabongs take first place at Zandvoort. Bhumibol put even more time into his photography and music, fancying a second career as a jazzman. [Handley, The King Never Smiles] Rama IX was also the most eligible Thai bachelor in the world. He was encouraged to meet several blueblooded young Thai women, and one of them charmed him above all others - Sirikit Kitiyakatra, daughter of Prince Nakkhat, Thai ambassador to Paris. In an interview for the 1980 BBC documentary Soul of a Nation, Sirikit recalled their first meeting in Paris: It was hate at first sight... because he said he would arrive at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. He arrived at 7 o’clock, kept me standing there, practicing curtsey, and curtsey. But in October 1948, Bhumibol crashed his car into the back of a truck outside Lausanne. Sirikit helped care for him during his recovery in Switzerland. She told the BBC: It was love... I didn’t know that he loved me, because at that time I was only 15 years old and planned to be a concert pianist. He was gravely ill in the hospital... He produced my picture out of his pocket, I didn’t know he had one, and he said: "Send for her, I love her." I thought of being with the man I love only. Not of the duty, and the burden of becoming queen. Bhumibol and Sirikit were engaged on July 19, 1949. And in 1950, the two set off to at last return to Thailand. Time magazine’s coverage of the country at the time was embarrassingly condescending its description of Thailand as “a land which most Americans are apt to regard as a musical-comedy setting” certainly holds true of its own coverage - and as Bhumibol sailed home it was not particularly complimentary about him either: Three times in the last three years the young (22) King had been rumored on the way home from the villa in Lausanne, Switzerland to which he went two months after his brother’s death. Three times something (a Siamese coup, an automobile accident or a mere change of plans) had interfered. Meanwhile, as the King spent his days going to school, organizing a swing band, tinkering with his cameras and driving his cars from Switzerland to Paris, royal duties piled up in Bangkok.

Last week gangling, spectacled Phumiphon was on the Red Sea in the steamship Selandia, with his pretty fiancée, 17-year-old Siamese Princess Sirikit Kitiyakara at his side. In Bangkok’s downtown dance halls, where Siam’s hepcats curve their fingers backward and dance the rumwong, the hit of the week was a song composed by the royal jitterbug Phumiphon himself: The little bird in a lonely flight Thinks of itself and feels sad . . .

The overwhelming majority of the people of Thailand did not share the magazine’s scepticism. Bhumibol received a rapturous welcome. On March 29. King Ananda was cremated. A month later, Bhumibol and Sirikit were married. And on May 4 and 5, Rama IX formally crowned himself king: The coronation on May 4-5 involved mostly inner-palace Hindu-based rituals evoking the devaraja cult: a ritual bath of the king in waters collected from auspicious sites, followed by the anointment of the king by Prince Rangsit representing the royal family, and an anointment by the sangharaja. The king then donned the royal robes and climbed atop an elevated octagonal throne, the faces of which represented the eight cardinal points of the compass, the expanse of his realm. He received homage at each side, a Brahman priest pouring holy water from 18 spiritually significant stupas. Then the president of the senate, representing the people, pledged the kingdom’s loyalty.

Bhumibol then moved to another throne, shielded by a nine-tier umbrella. The Brahmans presented him with the official royal regalia: his conical golden crown, the royal sword and cane, the whisk made from a white elephant’s tail hairs, a fan, golden slippers, and two rings of kingship. Kneeling, the priests recited Sanskrit incantations summoning the Hindu gods to descend and take up residence in his person. Bhumibol poured some holy water from a small ewer and, finally imbued with the correct spirit and tools to take the ultimate step, he crowned himself. Making a pledge to rule with justice, he scattered silver and gold flowers on the floor, symbolically spreading goodness over his kingdom.

Other holy acts, like formal horoscope reading and two hours of lying on the royal bed in the ceremonial residence of the king, sealed his deity. After two days, Bhumibol finally emerged in front of his subjects, accompanied by a trumpet fanfare and a cannon salute. The now fully crowned Rama IX declared that he was deeply attached to the Siamese people and would reign with righteousness, for their benefit and happiness. [Handley, The King Never Smiles] In an interview with New York Times correspondent Barbara Crosette in June 1988, Bhumibol was dismissive of the more arcane symbolism and rituals of his role, suggesting talk about this aspect of the kingship was exaggerated by the foreign media: ’’At first, it was all this rubbish about the half-brother of the moon and of the sun, and master of the tide and all that,’’ he says, in slightly accented English. ’’I don’t know where they found this I think they did it for my uncle, King Rama VII, when he went to America,’’ he says, adding that foreign correspondents, having made up those titles for a predecessor in 1931, continued to apply them to him in the 1950s. He considers it ’’irking.’’ ’’They wanted to make a fairy tale to amuse people - to amuse people more than to tell the truth.’’

Bhumibol was, of course, being disingenuous. He has always downplayed the ritualistic and spiritual aspects of the Thai monarchy when talking to a Western audience, but within Thailand he does exactly the opposite. In her thesis Thailand: The Soteriological State in the 1970s, Christine Gray identified an inescapable source of friction in Siam’s contacts with the West, which helps explain Bhumibol’s behaviour - and much else in Thai history and politics. She argues that a fundamental incompatibility or “antinomy” - between the universe that most Westerners believe in and the universe experienced by most Thais has been a source of constant tension since the two worlds first came into contact, and that this tension has been another influence on Thailand’s historical development. People around the globe may not be so very different, but there is often an enormous gulf between the cultural and spiritual universes they inhabit that can profoundly impact the way they interact: South and Southeast Asian cultural systems share a common cosmological framework, terminology, and emphasis on asceticism whereas Western and Thai-Buddhist cultural systems do not. The antimony theory was developed from the observation that the cosmology and symbolic systems of Western and Theravada Buddhist societies are so disharmonic as to be mutually negating. For a Thai-Buddhist king or Thai political leaders to advance or otherwise embody Western ideals or adopt Western speech styles is, in most cases, to automatically transgress indigenous ideals. The reverse situation also hold true: in many cases, for Thai elite to advocate or embody indigenous ideals in ruling the modern polity or in their interactions with Westerners is to automatically delegitimate themselves with that audience. [Gray, Thailand: The Soteriological State in the 1970s] The spiritual and cosmological foundations that underpin the monarchy are absolutely fundamental to an understanding of the role of the role of the palace in modern Thailand.

In the 1920s, a young British scholar called H.G. Quaritch Wales worked in the Lord Chamberlain’s Department in the Siamese royal court as an adviser to Rama VI and VII. In 1932 he published an exhaustive study of Thai royal ritual: Siamese State Ceremonies; Their History and Function. It is an extraordinary and explicitly political document. Written in the dying years of the absolute monarchy in Siam, it is infused with the conviction held by Quaritch Wales - and the kings and princes he worked for that “whereas it is good for Siam to make material improvements and break down old abuses it is, on the contrary, suicidal for her to interfere with her religion and cultural inheritance”. Quaritch Wales believed that reverence for the monarchy was utterly essential for Siam to prevent its people falling for the lure of dangerous ideologies of social equality. In the opening chapter he quotes - in horror - an item in the Bangkok Daily Mail from October 21, 1930: Owing to the failure of the public in general to give proper attention and due respect to His Majesty the King when the Siamese National Anthem is being played after performances in the local entertainment halls, H.R.H. the Minister of Interior has issued an order to police authorities to remedy the situation. It has been noticed that when the band strikes up the National Anthem some persons seem to pay little attention it it, while others walk out of the hall, quite oblivious to the patriotic custom. To Quaritch Wales, this was clear evidence that Siam was on the road to ruin: In the days of Old Siam there was no National Anthem. But had there been one, or had the people found themselves in the presence of a Royal Letter or any other symbol of royalty, they would have known quite well what to do. They would have immediately thrown themselves flat on their faces. That custom was abolished long ago in accordance with the needs of a new age. But what was left in its place? … Though the people are at present absolutely devoid of evil intent. the door is left open for the dark teachings of communism, or whatever doctrines may chance to catch the ear of the masses, to step in and hasten the work of social destruction. The young British scholar goes on to explain why, in his view, the monarchy is essential for social order in Siam. Tracing the history of the Thai people “in the course of their evolution from a tribe of nomads in southern China to their present position as the rulers of the modern kingdom of Siam” he says that in the world of “Old Siam”, from the earliest days of the Ayutthayan kingdom in the 14th century to the rule of King Mongkut, Rama IV, in the mid 19th century, a deeply rooted terror and respect for authority was engraved into the psyche of the people of the kingdom: In Old Siam the inhabitants of the country were considered only as the goods and chattels of the king, who had absolute power over their lives and property and could use them as best suited his purpose. Otherwise they were of no importance whatever...

The absolutism of the monarch was accompanied and indeed maintained by the utmost severity, kings of Ayudhya practising cruelties on their subjects for no other purpose than that of imbuing them with humility and meekness. Indeed, more gentle methods would have been looked upon as signs of weakness, since fear was the only attitude towards the throne which was understood, and tyranny the only means by which the government could be maintained... Despite the fact that all were equally of no account in the presence of the king, a many-graded social organization had evolved, and the ingrained habit of fear and obedience produced a deep reverence for all forms of authority.

Near the top of the hierarchical pyramid - though still far below the lofty realm of royalty - were minor nobles and bureaucrats, and below them the rest of the people, branded to make clear their status as the property of the state: All these officials were continually occupied in showing the necessary amount of deference to those above them, and to the king at the top, while mercilessly grinding down those below them in the social scale... The great mass of the people were divided into a number of departments for public service... the members of which were numbered and branded by the noblemen in charge of each department. The luckier ordinary citizens could escape compulsory obligations to the state in return for paying tax. As for the rest: The vast majority of the people... were collected in rotation as required, obliged to serve as soldiers, sailors and other public menials... for whom no escape was possible, the status being hereditary.

At the very bottom of the heirarchy were slaves, although Quaritch Wales says reassuringly that “it must be added that Siamese slavery was always of a very mild type”. Thailand’s King Chulalongkorn, Rama V - grandfather of both Bhumibol and Sirikit - launched a dramatic modernization of Siam, something Quaritch Wales appears to feel rather ambivalent about: The reforms of King Rama V brought about great changes, many of them for the better, in the life of the Siamese masses. One of the most far-reaching of these was the abolition of slavery; another was the abolition of bodily prostration of inferiors in the presence of their superiors. Despite efforts to modernize the monarchy and Siam’s social structures as the kingdom came into increasing contact with the West, Quaritch Wales argues that the country’s people still maintained enormous reverence for royalty after many centuries of brutal tyrannical rule: So great, it might be added, are these hereditary instincts, that bodily prostration still lingers to some extent, although it is, of course, entirely voluntary. Siamese servants often crouch in the presence of their masters, officials lie almost full length when they are offering anything to the King on his throne and I have seen ladies of the older generation crawling on their hands and knees when in the presence of a prince of high rank with whom they held conversation, with their faces parallel to the ground, while the prince was seated in a chair. While the old instincts thus lurk so closely below the surface there can be no doubt but that the monarchy still remains the most important factor in the Siamese social organization.